It can be kind of intimidating when you are first learning how to improvise in a jazz context. After learning all of your scales, chords, and modes, you might feel confused about how to proceed when faced with a lead sheet. Should you use a scale or an arpeggio over a chord change? What mode works? The challenge of improvisation might seem insurmountable.

But developing jazz vocabulary doesn’t have to be an intimidating process – it can actually be fun, even if you have to go about it in a methodical way. Here, I will demonstrate a simple method that you can use to start developing vocabulary.

When I’m working with beginning students of jazz, I always like to start with the blues because it has minimal chord changes – and it’s an essential form in jazz. I think it’s best to start with simple changes and slow harmonic motion.

- Let’s start with the right hand.

While it’s certainly important to be able to play voicings with the left hand, too often it distracts us from the process of making melody. In order to be able to comp well, you should first have a conception of a melody to comp for.

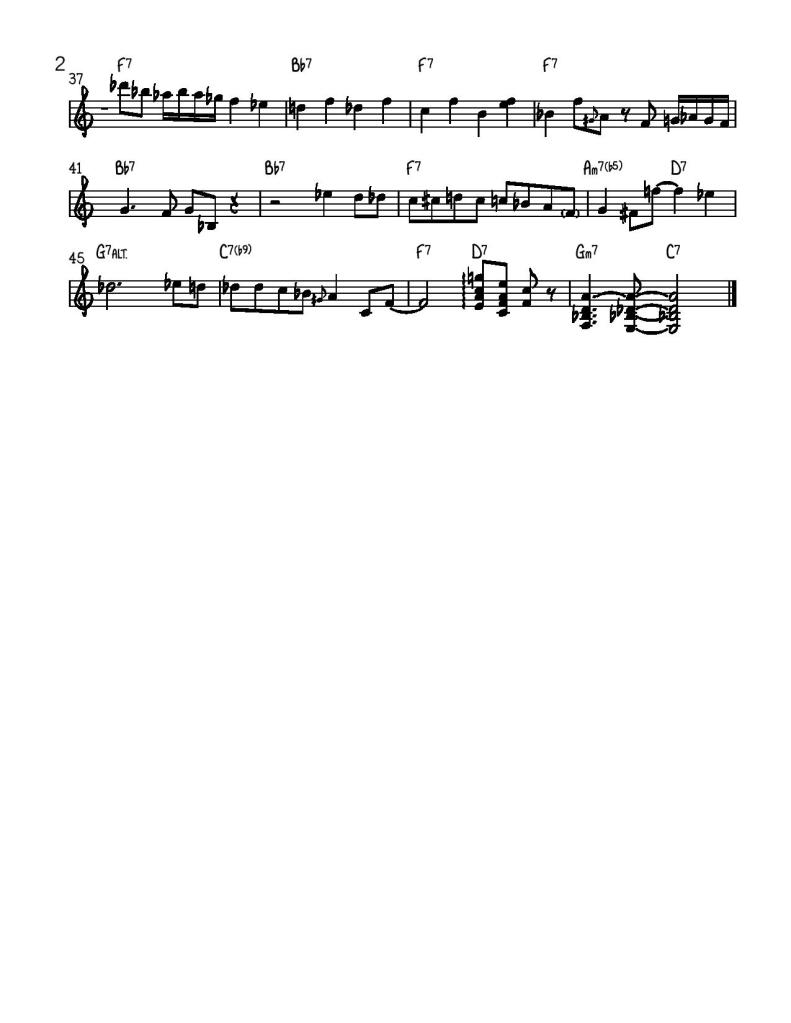

As for solos, I like to start people off with the great John Lewis. While he is most well known for the Modern Jazz Quartet, he began his long, illustrious career playing on iconic Charlie Parker albums. Lewis has a simple, elegant conception of melody, and he uses a lot of eighth notes and quarter notes, rather than triplets and sixteenth notes. Here is a process for mining his solos and jump-starting your improvising subconscious:

- Learn the solo and play along with the recording until you have mastered the phrasing and feel

- Practice playing two bars of the solo and then omitting the next two bars (try to “answer” with your own material) – you can also practice playing just the even measures, or the odd measures

- Circle three licks that you like in the solo, transpose them into all keys

- Apply your chosen licks to other parts of the tune (e.g., if there’s a lick over an F7 that you like, plug it into another part of the tune with the same chord change)

- Write your own solo using the licks that you chose. It will help if you have transposed them into every key.

That’s it for now! If you have any questions, send me a message.

You must be logged in to post a comment.